Album of the Week, February 21, 2026

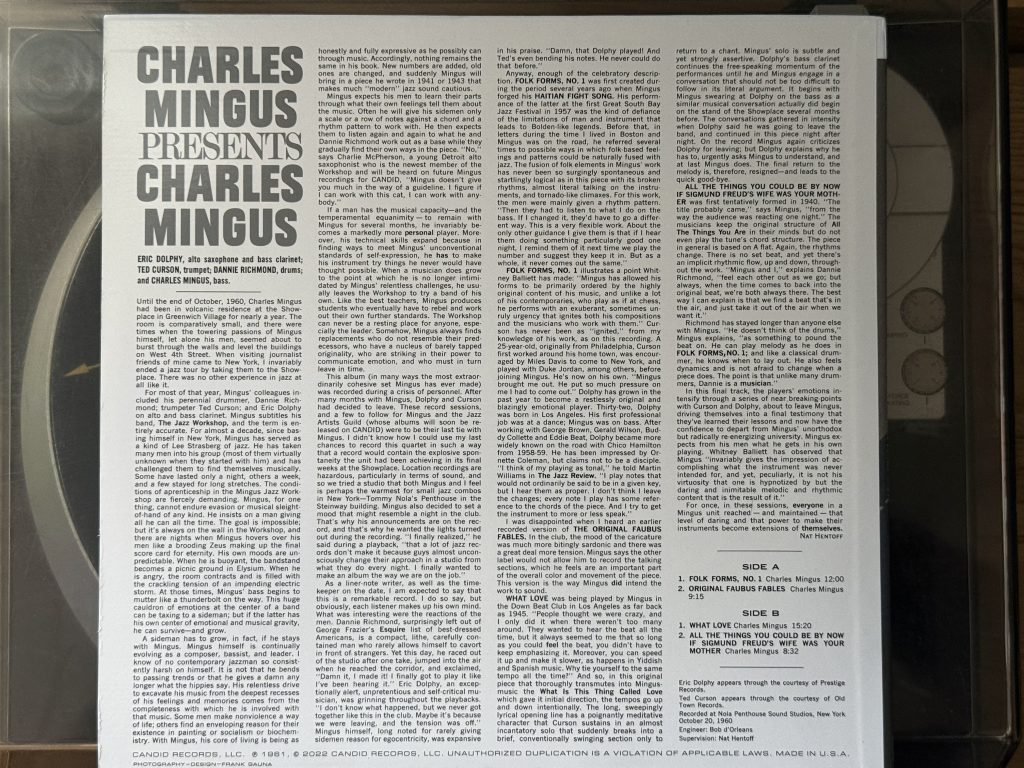

Charles Mingus was unwell. The cruel progression of ALS had robbed him of most of his technique on the bass, and of his ability to stand. But he could still play, a bit, and he could lead a band. And so he brought a nonet (and later a, um, tentet) to a New York City studio on March 9-10, 1977 to record tracks for what would become one of his last albums.

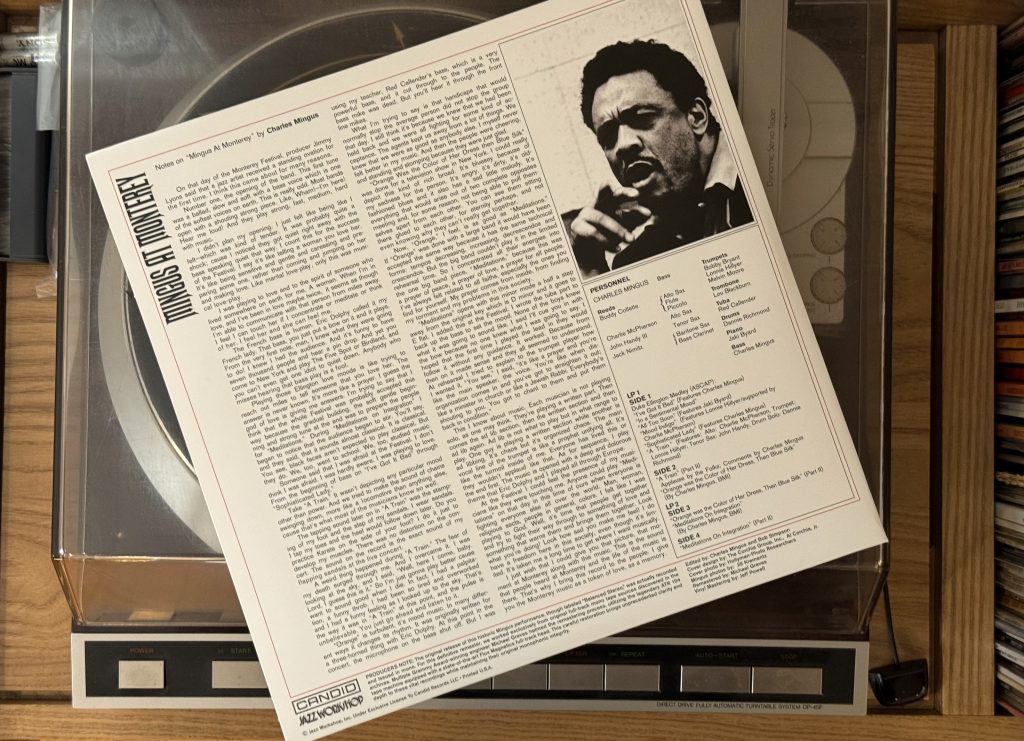

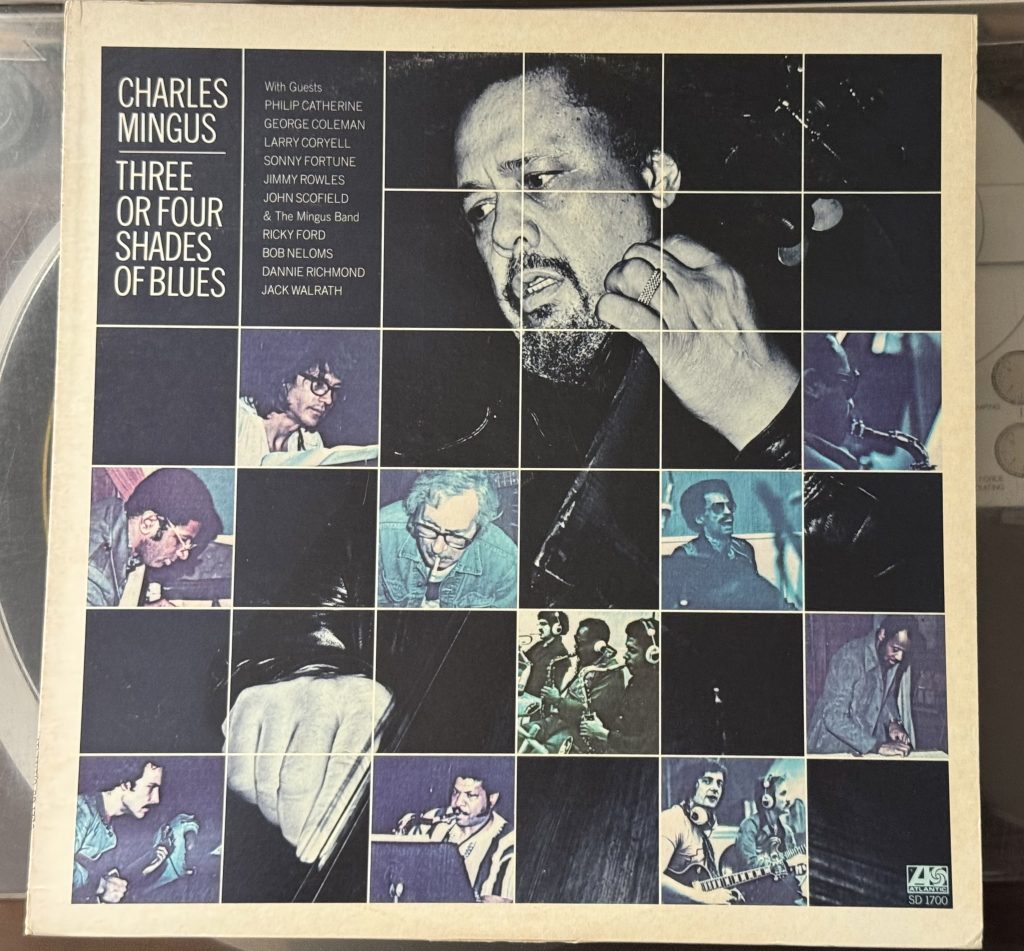

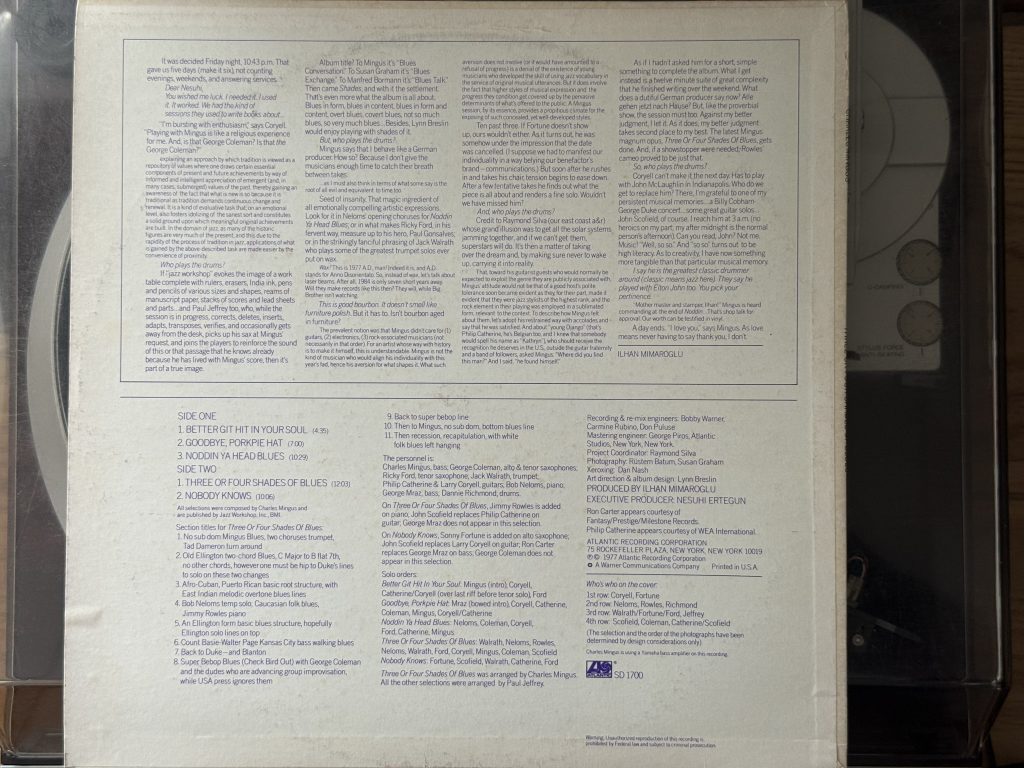

Behind the drums sat the redoubtable Dannie Richmond; almost every other musician was a new face for this column, though he had been touring with some of them for years. Jack Walrath (trumpet) and Ricky Ford (tenor sax) were part of his regular touring band, but Bob Neloms was a new face at the piano. Bowing to necessity, George Mraz sat in at bass for the first three tracks, supporting Mingus. Not one but two electric guitarists, Philip Catherine and Larry Coryell, play on the majority of the tracks; John Scofield replaces Catherine on one track and Coryell on another. A second sax player was there too: George Coleman, who after leaving Miles’ band in February 1964 had become an in-demand player, to the point that Coryell is quoted in the liner notes as saying “Is that George Coleman? Is that the George Coleman?” A second piano player, Jimmy Rowles, appears on the long track “Three or Four Shades of Blues,” and Sonny Fortune’s alto sax is on the last number, along with Ron Carter who replaces Mraz.

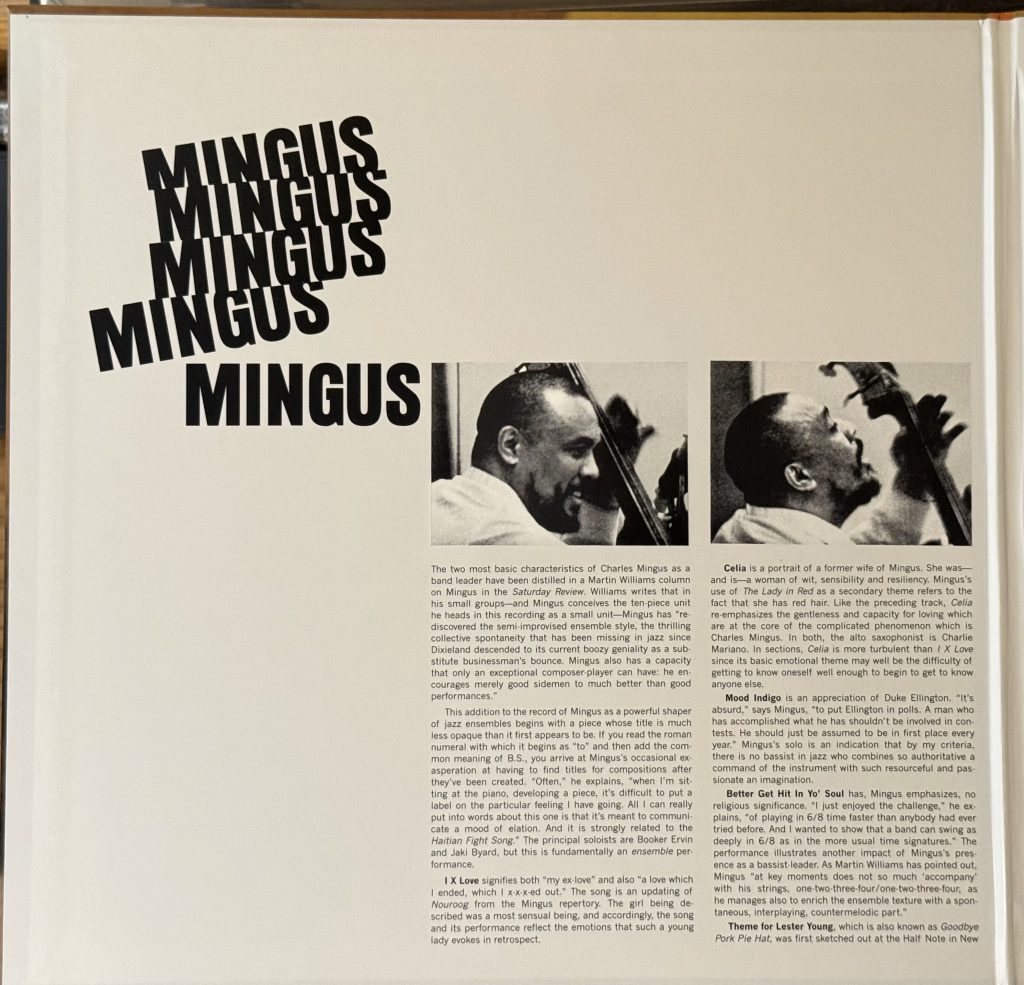

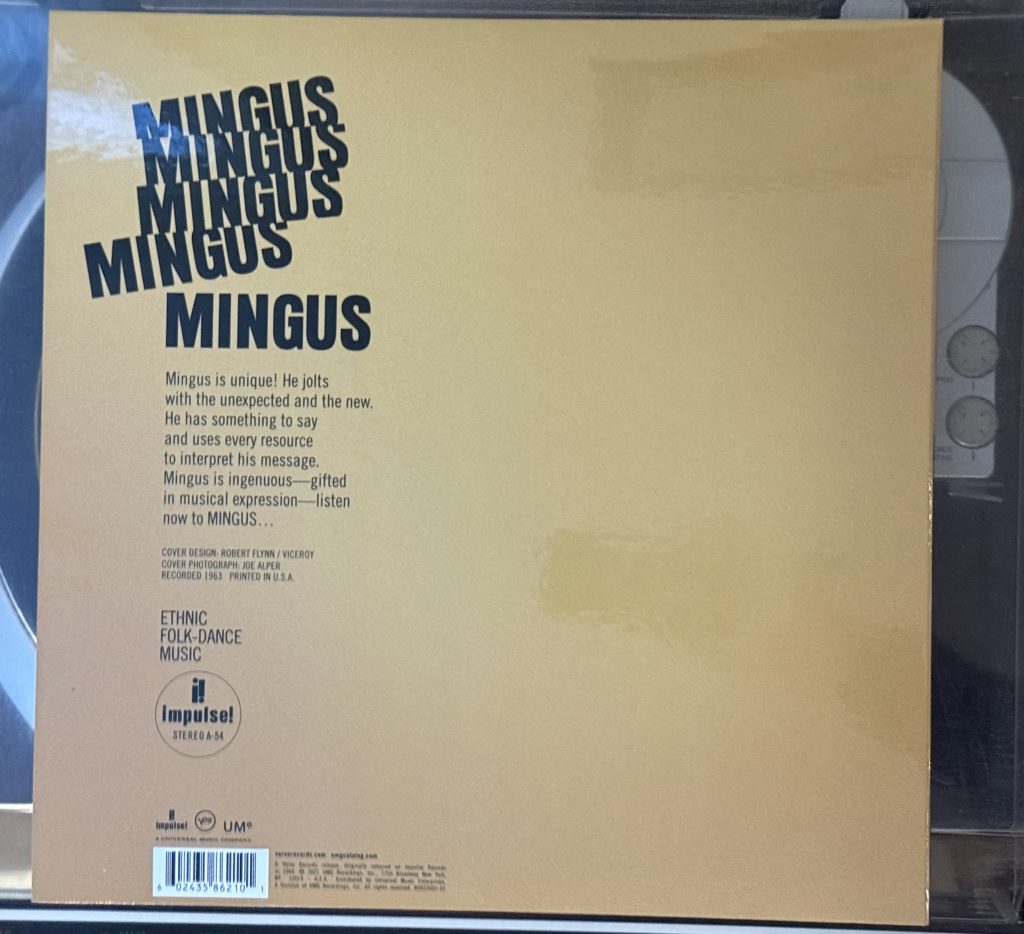

One could look at the track list, see the first two tunes, and assume that this was another “greatest hits” set with a different band. But there’s a completely different energy here from Mingus Mingus Mingus Mingus Mingus. “Better Get Hit In Yo’ Soul” gets a better recording of Mingus’s opening bass line, for one thing, which he rips into with alacrity. And the whole temperature is elevated about ten degrees (Fahrenheit) by the two guitarists, particularly Coryell, whose solo is electrifying. There is also, unusually for this tune, a fully sung lyric on the chorus, by the entire band: “He walked on water. He ministered to the blind. He healed the sick. And he raised the dead. Talkin’ ’bout Jesus!” Ricky Ford’s tenor gives a down-home and gutsy R&B solo before taking off into a Trane-inspired series of glissandi over general mayhem in the band. Neloms hammers the keys into the last bridge as the two guitarists play blasts of chords and Jack Walrath lets loose with an apocalyptic squawk. This is Mingus as gateway to the universe; probably why this was the only track of his that made it onto one of my mix tapes as a college student.

“Goodbye Pork Pie Hat” is given a subtler read. George Mraz introduces the tune, arco; and the guitarists play the melody alongside him. The guitarists are playing classical style this time, and Coryell’s virtuosity here is gorgeous but quieter; Catherine’s is practically Spanish in its precision. George Coleman provides an impeccably brilliant tenor solo leading into a key change and Mingus’s harmonically rich exploration. The two guitarists play in duet to close the solo section, leading into the final chorus and a long coda that is both wearily beautiful and impossibly sad.

“Noddin’ Ya Head Blues” takes us into a twelve-bar blues by way of a gospel-inspired Neloms piano solo, punctuated by bursts of Coryell and leading into the melody stated by the two guitarists. Coleman gets a flutteringly beautiful solo that he passes virtuosically to Coryell, who does a combination of Hendrixesque flourishes and dirty Delta blues. Ricky Ford’s solo is restrained by comparison here, but yields to Philip Catherine for a twelve-bar Spanish romp that falls away for Mingus’s slow and low solo, accompanied by Mraz and Richmond up to the final chorus.

“Three or Four Shades of Blues” is programmatic music, with the program helpfully spelled out in the liner notes: “No sub dom Mingus Blues; Old Ellington two-chord blues; Afro-Cuban; Caucasian folk blues; An Ellington form basic blues structure; Count Basie – Walter Page Kansas City bass walking blues; Back to Duke – and Blanton; Super Bebop Blues (Check Bird Out); Back to super bebop line; Then to Mingus, no sub dom, bottom blues line; Then recession, recapitulation, with white folk blues left hanging.” At least three or four shades of blues, indeed. There are some ingenious twists and turns in this music, especially the pivot into Afro-Cuban blues and the cheeky quote of the Mendelssohn wedding march (the Caucasian blues!). For my money this is not one of Mingus’s most essential long-form works, but it might be among his most approachable, particularly in the “super bebop” section.

“Nobody Knows” is credited to Mingus, but it incorporates bits of “Nobody Knows the Troubles I’ve Seen” and “Down by the Riverside” in its brisk melody. Sonny Fortune’s sweet alto soars across the band, leading to John Scofield’s precise blues and Jack Walrath’s trumpet, here brisker and more precise than in his other featured spots. Solos from Philip Catherine and Ricky Ford round out the tune in a valedictory send-off.

Mingus recorded two more albums following this one, but his health was going downhill fast. In 1978 he was invited to the White House as part of a ceremony honoring 25 years of the Newport Jazz Festival, where he was lauded by an enthusiastic Jimmy Carter; the moment moved Mingus, now confined to a wheelchair, to tears. He worked in his last days on a project with Joni Mitchell, which she completed after his death as her album Mingus. In late 1978 he traveled to Cuernavaca, Mexico to seek treatment and rest from his disease, and he died there on January 5, 1979. He was only 56 years old.

Mingus stands alone for many reasons: his fierce iconoclasm, his dogged insistence in pursuing his own vision, and the degree to which he succeeded in realizing that artistic direction during his short lifetime. Next week we’ll pick up a different thread that begins with another 1977 album, following the life of another iconoclastic musician who might be as well known for his knack of finding and promoting brilliant collaborators as his own distinct genius.

You can listen to this week’s album here:

BONUS: A short segment from a longer documentary about the Newport Jazz Festival featured these moments of broadcast video about the White House reception, including a few precious seconds of Mingus, overcome by Carter’s praise of his work.