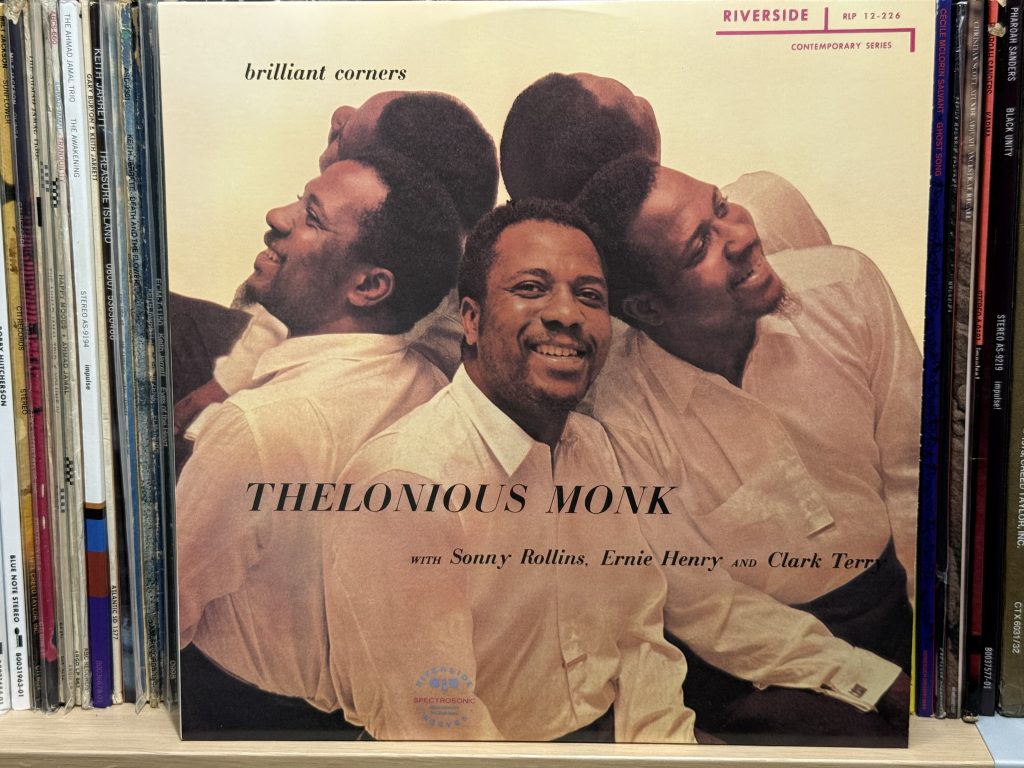

Album of the Week, July 12, 2025

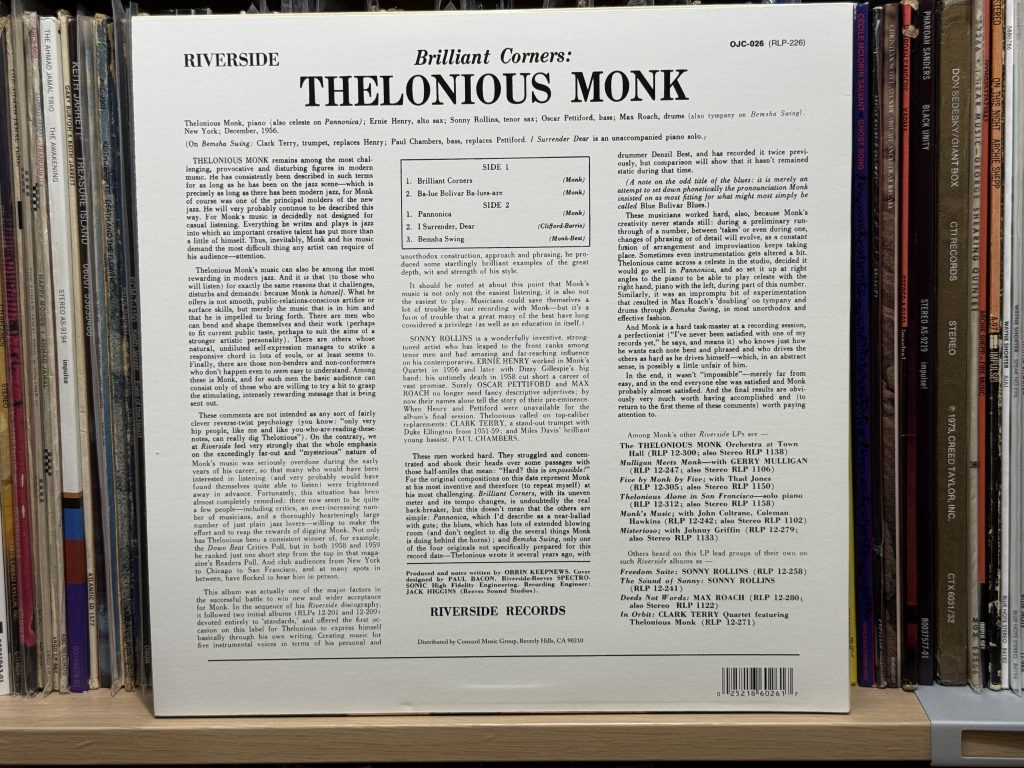

Thelonious Monk followed up the 1955 pair of standards albums (recorded as his first for Riverside Records) with a bang. Brilliant Corners consists of five Monk originals, of which only “Bemsha Swing” was previously recorded, and with a title track so complicated that producer and Riverside founder Orrin Keepnews had to assemble it from multiple takes. But unlike previous Monk outings that were doomed to obscurity, Corners was a critical smash hit, with Nat Hentoff calling it “Riverside’s most important modern jazz LP to date.”

The album was recorded in a trio of late 1956 sessions, with slightly different personnel. The October 9 and 15 sessions featured a quintet with Sonny Rollins and Ernie Henry on saxophone, Oscar Pettiford on bass, and mighty bebop drummer Max Roach. A follow-up session on December 7 saw trumpeter Clark Terry replacing Henry and bass giant Paul Chambers replacing Pettiford.

“Brilliant Corners” begins slowly, as if the band is learning the melody by rote, following Monk’s initial solo statement, and then taking it through a series of key changes until it gets back to the beginning. But once that initial statement is underway, they restate the theme in double-time, demonstrating the band’s virtuosity as well as the difficulty of the composition. Rollins takes the first solo, playing ahead of and behind the beat in the single time section and unleashing a series of blisteringly fast improvisations in the double-time. Monk’s solo plays through the melody and demonstrates an unconventional solo technique on the fast passage: he plays a few bars, drops out, then reenters a few bars later with a blistering attack. Ernie Henry’s solo is fat, soulful, and not nearly as facile with the material as Rollins; the story goes that Monk dropped out under his solo to keep from distracting the alto player. He was not the only one to explore silence in the complex tune; the story goes that Orrin Keepnews had to check the microphones on Pettiford’s bass after one take, only to find that the otherwise highly skilled bassist was actually miming. The magnificent Max Roach seems fully at ease here, unleashing a blistering, melodically rich solo before the last chorus. Notoriously, the group never finished a complete take of the number; Keepnews assembled the version on the record from several fragmentary takes of the number. That may be so, but it’s a brilliant (no pun intended) assemblage.

“Ba-Lu Bolivar Ba-Lues-Are” (Monk’s phonetic rendering of the “Blue Bolivar Blues”) is named after the Bolivar Hotel, the Manhattan home ground of his patroness, the Baroness Pannonica de Koenigswarter. The tune starts as a simple enough blues, but Ernie Henry’s smeary bebop improvisation over Roach’s precise stumble of a drum accompaniment quickly shifts it into something more. Monk’s imaginative and complex solo illustrates both his genius and his flat-fingered playing style, which often resulted in his hitting seconds and famously led to his assertion that “there are no wrong notes on the piano.” As if to underscore the genius of his approach, there are also virtuosic passages that introduce completely new melodies, one of which Sonny Rollins takes as a point of departure for his own solo. As before, Roach unleashes fusillades of snare sound under Rollins’ flights of improvisational fancy. Pettiford demonstrates his usual aplomb in an extended solo that leans into the blue notes of the tune.

“Pannonica” is an example of that most underappreciated of compositional categories: the Monk ballad. Played on the celeste rather than the piano by the composer, Monk introduces the melody dedicated to his patroness before the full ensemble joins and states the theme. Monk plays it more or less straight, with a few flourishes around the edges and the sliding chromaticism of the tune the only clues that we are in his genius realm. Sonny Rollins takes the first solo, seemingly at double tempo, though in reality the chords of the tune move at the same tempo as of the introduction; it’s just that he switches from quarter to eighth notes, as it were. Underneath him, Monk switches to the piano more or less undetected; one wonders whether this magic was accomplished with a swiveling chair or by the keen editorial hand of Keepnews. That it’s all live is eventually given away (and described in the liner notes) as Monk plays the second 16 bars of his solo with left hand on the piano keyboard and right hand on the celeste, before returning to all-piano to close out his solo. He moves back and forth between the two instruments in the final reprise, throwing high accents on the celeste and closing out with a repeated high arpeggio on a suspension, as we end the side.

“I Surrender Dear” is a pure Monk solo, recorded during the December recording session. Written by Harry Barris with lyrics by Gordon Clifford, the song appears to have struck a spark in Monk’s imagination, as he covered it several times in his recording career. We get all the Monk highlights here: the shift from stride into an almost hesitating rubrato that occurs even during the first statement of the theme; the introduction of an out-of-time series of arpeggios to accent the dramatic shape of the melodic line; and of course the Monkian splatted seconds that add so much to the color of the playing. At the end, Monk seems to drift away into a reverie of a different song altogether. For a cover song, it’s as pure a statement of Monk’s method on record as I know.

“Bemsha Swing,” the other song from the second session, brings Terry’s brilliant trumpet to the group. Terry had previously played for Charlie Barnet and Count Basie, but he was in Duke Ellington’s band at the time of this recording. (He would later be in the Tonight Show band for ten years and play with Oscar Peterson for an astonishing 32 years; he’d outlive most of the players on this session, dying in 2015.) This is the only of Monk’s compositions from this record to have appeared previously, recorded for his Thelonious Monk Trio record for Prestige in 1952. Monk essays the melody as a series of rising fourths in a sort of stumbling fanfare, then firmly states it in the opening proper. There’s both stumbling (virtually, via some impressive syncopation) and firmness in what follows, particularly from Roach, who seems to be playing cymbals and snare with one hand and foot and tympani with the other hand throughout. Chambers is completely unfazed by the melodic complexity, sliding through the changes without breaking a sweat. Likewise, Rollins appears completely at home here, essaying a series of improvised double-timed thoughts that unroll as a continuous melody over the chords. Terry follows Rollins’ lead but switches it up with some longer held notes and some judicious rhythmic pauses between phrases. Monk’s solo occasions both some out-there high improvisation and some of Roach’s finest work on the record, as he alternates some fine snare work with emphatic pronouncements on the timpani, both in time and in hemiola. Chambers takes a solo that alternates walking the changes with statements of the melody, and Rollins picks things up in media res. Monk joins Rollins for the second verse of his solo with his own improv, and Terry comes in seamlessly to single the final chorus. There are many fine examples of collective improvisation in recorded jazz history, but I’m fairly certain there are no finer moments in Monk’s recordings to this point.

With Brilliant Corners, Monk had finally tipped the balance on the critical appraisal of his works, and his compositions and recordings began attracting more favorable notice. This affected not only his freedom to record but also the players he attracted. It was two short months after the April 1957 release of the record that he recorded Monk’s Music with John Coltrane and Coleman Hawkins. There followed a series of studio and live recordings for Riverside that ended in a royalty dispute. But Monk wasn’t done yet; his biggest selling recordings were ahead of him. We’ll hear one of those next week.

You can listen to this week’s album here:

BONUS: Thanks to the archival work done to assemble various biopics of Monk, we have a recording of Monk playing “Pannonica” for his patroness shortly after he wrote it, including his spoken introduction. There’s so little of Monk’s spoken voice out there that this is a rare treat indeed.