Album of the Week, July 5, 2025

We’ve written about a lot of musicians in this series. There have been heroes, back room figures, producers, composers, soloists and sidemen. There’s one whose work has been touched on a few times, but who has only appeared in these virtual pages one time as the leader of his own group—and in that write up, I was mostly focused on his sideman. That man is Thelonious Sphere Monk.

When I reviewed Monk’s Music, I started in the middle of his story, so let’s step back to the beginning. Born in 1917 in Rocky Mount, North Carolina, a city east of Raleigh known for cotton, tobacco, racial segregation, the civil rights movement and the original headquarters of Hardees, Monk and his family relocated to the Phipps Houses in the San Juan Hill neighborhood of Manhattan when he was five. He learned piano from a neighbor, Alberta Simmons, beginning at age nine. Simmons taught him the stride piano style of Fats Waller and James P. Johnson, as well as learning to play hymns from his mother. He attended Stuyvesant High School but left to focus on the piano. He put his first band together at age sixteen and honed his chops in “cutting contests” at Minton’s Playhouse, where the new jazz form of bebop took shape in jam sessions that included Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Bud Powell, Kenny Clarke and Charlie Christian. (Minton’s is, improbably, still around today.)

Monk was a psychiatric reject from the US Army and was not inducted into the armed services during World War II. He played with Coleman Hawkins, who promoted the young pianist, and made the acquaintance of Lorraine Gordon, the first wife of Blue Note Records founder Alfred Lion. Gordon became the first of many to champion Monk’s work to an initially resistant public. She recounted trying to convince Harlem record store owners to carry Monk’s records, only to be told, “He can’t play, lady, what are you doing up here? That guy has two left hands.” Gordon helped Monk secure his first headlining gig at the Village Vanguard, a weeklong engagement to which, reportedly, not a single person came.

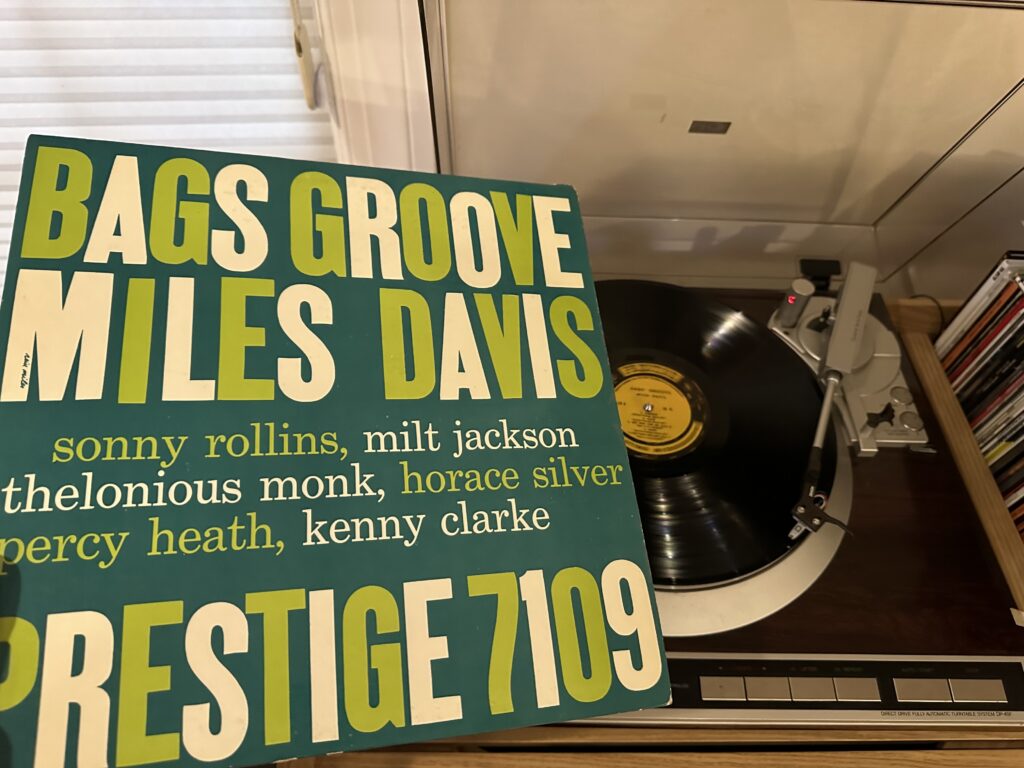

The bottom came, as previously recounted, when Monk’s car was searched and police found Bud Powell’s drugs; Monk refused to testify against his friend and lost his cabaret license, costing him the ability to play in any licensed nightclub that served liquor. He got by playing guerilla shows at Black-owned illegal clubs, but the loss of venues hurt his already struggling recording career even more. In 1952, he began recording for Prestige Records, cutting several pivotal but underselling records, including a 1954 Christmas Eve session with Miles Davis that produced Bags Groove.

By 1955, Monk was highly regarded but broke, and the turning point came when Orrin Keepnews’ Riverside Records bought out Monk’s contract from Prestige for a mere $108.24. Keepnews took the challenge of marketing the eccentric Monk head-on. Reasoning that listeners stayed away from Monk due to his reputation for difficult music, Keepnews convinced him to record an album of Ellington tunes; as the producer recounts in the liner notes, “he retired briefly with a small mountain of Ellington sheet music; in due course he reported himself ready for action; and thus this LP was born.” Monk was accompanied by bebop giants Kenny Clarke on drums and Oscar Pettiford on bass. The album’s initial 1955 release featured photos of the three players; the 1958 reissue shown above has a portion of the Henri Rousseau painting The Repast of the Lion.

Monk begins with the well-known “It Don’t Mean a Thing (If It Ain’t Got That Swing),” opening with the scatted tag-line from the refrain. He leans forward into the syncopation until it’s almost but not entirely straightened out; plays fistfuls of cluster chords under the chorus; but otherwise plays the tune pretty straight. There’s a nifty countermelody that comes out in the second verse, riding in on the back of a triplet flourish, and a burst of stride in the last chorus. In other words, it’s pure Monk.

“Sophisticated Lady” is a tougher challenge for the album concept, as Ellington’s melody has to keep its sophistication and its savoire-faire even with Monk’s unusual approach to the keys. Monk nails the assignment, albeit with some unusual rhythmic approaches. The sequence of downward glissandi in the B section, the trills and slightly off accent notes that read a little like stride piano heard through a skipping record player, all add to the general Monk flavor while honoring Ellington’s basic melodic sensibility.

“I Got It Bad (And That Ain’t Good)” calls to mind Marcus Roberts’ later homage to Ellington (surely Roberts listened to this recording). Here Monk begins alone, playing the Ellington classic as though it were a sonata, with an unexpected tenderness despite the clusters of chords under the melody. When Pettiford and Clarke join in, the tempo picks up and Monk begins to explore the contours of the verse. His final essay climbs the octave chromatically, sounding a wistful note.

“Black and Tan Fantasy” opens in an unusual place, exploring the funeral march quote that Ellington ends the piece with. Where forty years later Marcus Roberts played this tune with a heavy debt to the stride tradition, Monk’s version is considerably more subtle, exploring the chromaticism and major-to-minor flourishes in Ellington’s tune.

Monk begins “Mood Indigo” with an imaginative vamp on the I – dim VI – VI portion of the tune’s famous chorus, underpinned with a syncopated running pattern. He takes the tune more or less straight, but with embellishments at the turns that could have come straight out of Erroll Garner were it not for the unusually crunchy chord voicings. A word must be said about Pettiford’s playing here; he not only keeps up with Monk’s imaginative chordal gymnastics but also picks up on his rhythmic variations, all the while sounding completely unflappable.

“I Let a Song Go Out of My Heart” borrows the same trick that Monk used to begin “Mood Indigo,” a little riff on the closing triplet bit of the chorus. Here Monk uses the brisker tempo of the standard to keep the triplet meter running as a commentary throughout, and we get some real moments of virtuosity (“two left hands,” indeed!). This piece is also a showcase for Pettiford, as he not only plays the melody but gets a few verses of improvisation. Monk picks up the running triplet meter again into the back of the tune, and ultimately lands it with a series of chords up to a resolution. This is as close to jolly as I’ve heard Monk on material other than his own. It’s a blast.

“Solitude” is more exploratory and more introspective, as Monk takes the tune more or less directly, albeit with some rhythmic commentary from the left hand in the beginning. He takes this one completely solo, and takes advantage of the opportunity to slow into the end of the last chorus and finish with some delicious rubato.

“Caravan” is Kenny Clarke’s moment to shine, with a polyrhythmic energy driving the classic tune from the first beat. Monk gives him room in the wide expanses of the chorus for his rhythmic explorations, and takes his turn in the verse. In the second chorus, Pettiford takes a forthright solo on the higher strings and shows how his imagination and virtuosity contributed to the bebop movement. Finally, Monk takes the lead once more and gives us a whirling-dervish finale. It’s as though the camels stepped onto the dance floor for one last boogie before the groove ran out on the record.

Keepnews’ instincts as a producer were sound. By subtracting one element from the rich and strange brew of Monk’s overall conception, he found a way to allow Monk the pianist to put his distinctiveness forward in material with which the general listening public was familiar. A second album of standards followed later in 1955, and by the time the third album came along in late 1956 the listening public was primed to hear Monk’s full artistic direction. We’ll hear that album next week.

You can listen to this week’s album here:

BONUS: Monk continued to play some of the tunes on this album throughout his career, albeit in different conceptions. Here’s a great concert video of him performing “Caravan” solo, live in Berlin in 1969.