Album of the Week, June 14, 2025

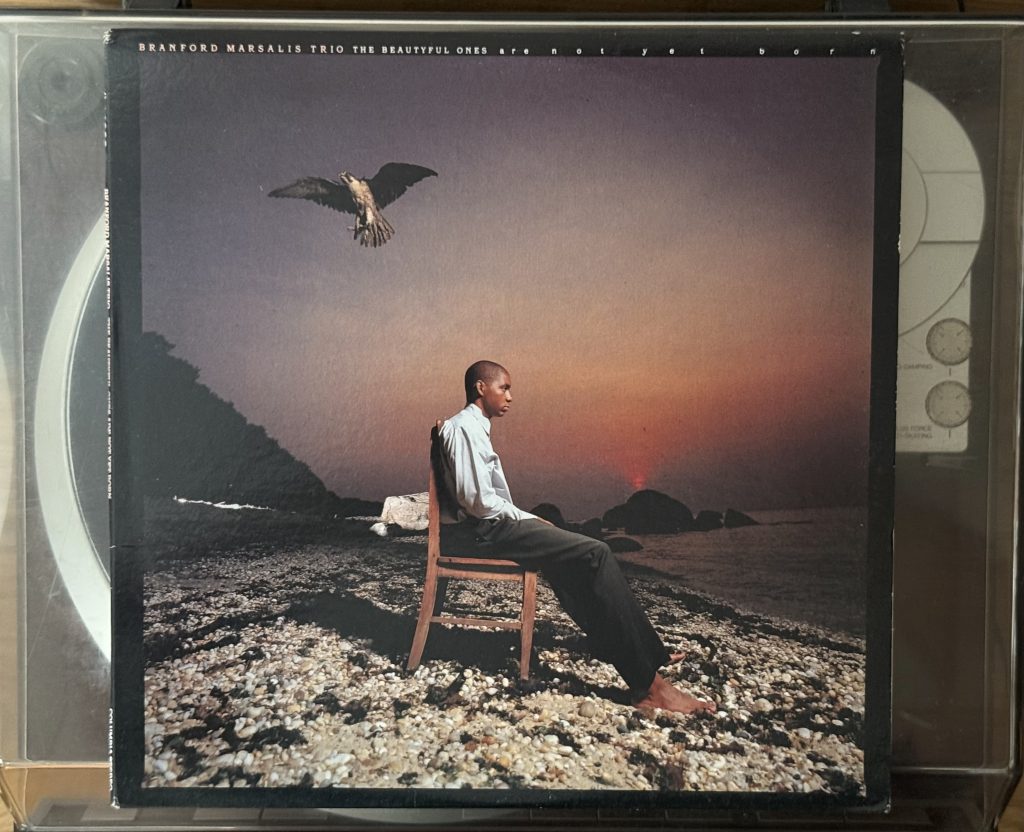

Branford Marsalis had built two brands by the time 1991 rolled around. He was still appearing periodically with Sting, most recently on the rocker’s concept album The Soul Cages, and in 1990 had started to perform from time to time with the Grateful Dead, even appearing on their 1990 live album Without a Net. But he also had an increasingly solid run of more traditional jazz albums to his name, and his most recent one, Crazy People Music, had hit Number 3 on the Top Jazz Albums chart and been nominated for a Grammy award for Best Jazz Instrumental Performance, Soloist (he lost to Oscar Peterson). In this context, his 1991 album, The Beautyful Ones Are Not Yet Born, feels a bit like a statement that he had serious things to say about jazz.

In Branford’s earlier albums you can hear his influences at work, with a solid Wayne Shorter and Ornette Coleman, to say nothing of Ben Webster and Jan Garbarek, on display in Random Abstract. Those influences were consolidated into Branford’s own musical conception by the time of Crazy People Music, and on The Beautyful Ones we’re in an entirely new landscape, by turns bleak, playful and primal in its approach. We’re also in a land of burnout, in the sense coined by Ornette Coleman, in which the soloists take their improvisations as far as they can go rather than being constrained by bar counts. This record is as close to free jazz as Branford had gotten to this point in his career.

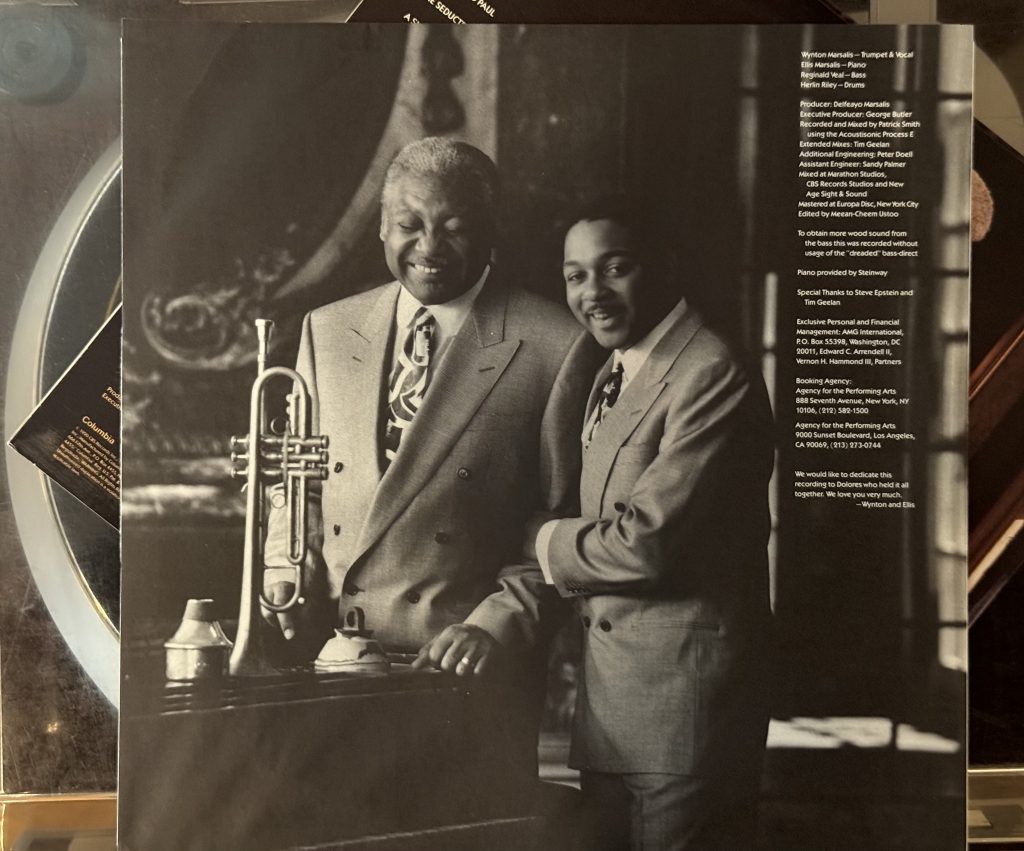

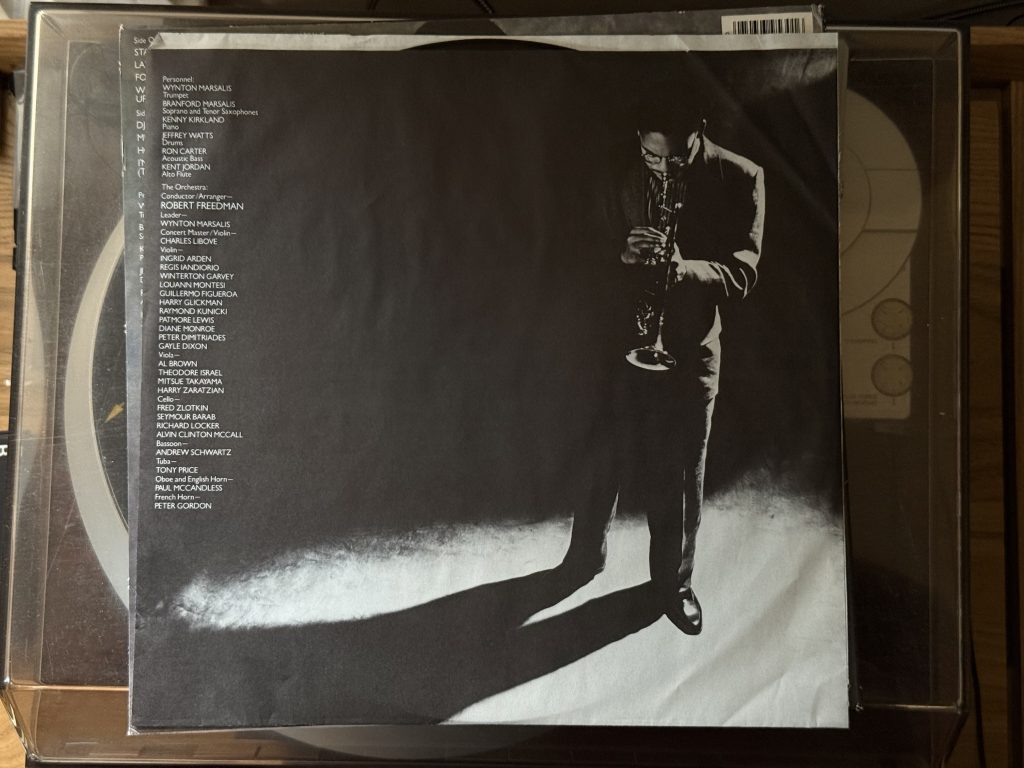

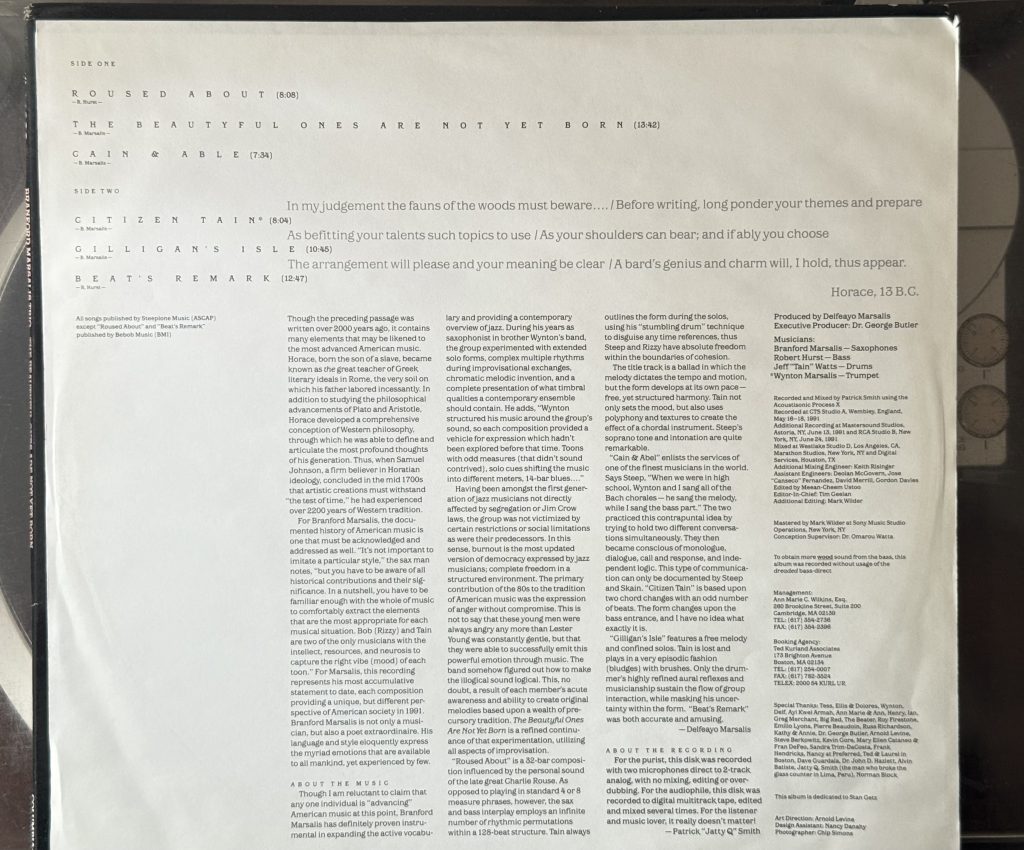

As with Trio Jeepy, he was without frequent collaborator Kenny Kirkland on this one;1 the trio included Branford, Jeff “Tain” Watts on drums and Robert Hurst on bass. Younger brother Wynton shows up for a tenor/trumpet battle on “Cain and Abel,” and Courtney Pine appears on a CD-only bonus track. For the most part, though, you just get the trio, giving them an enormous amount of freedom to explore their sonic world.

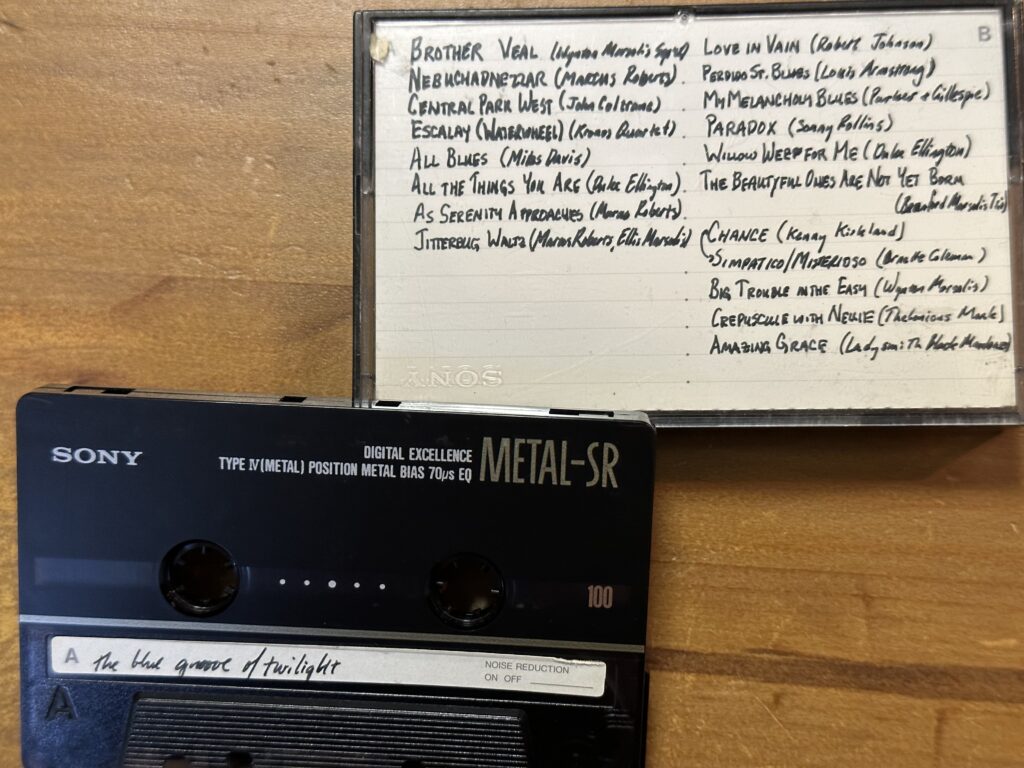

“Roused About” opens with a Robert Hurst-penned tribute to Charlie Rouse, the tenor saxophonist who collaborated with Thelonious Monk from 1959 to 1970. Like the best of Rouse’s playing, Branford’s solo statement of the melody here is all angles and unexpected austere turns, but it’s also deeply swinging and convincingly melodic, in spite of the odd modal twists of the melody. Bob Hurst plays a sort of omnitonal walking bass that never stops moving but also seems to never settle down into one key. Likewise, Jeff “Tain” Watts gives us a sort of shambolic swinging pattern on cymbals and snare, what Branford’s brother Delfeayo calls in the liner notes his “‘stumbling drum’ technique.” But it’s a whistleable melody and a genuinely fun performance.

There’s also a strong melody in “The Beautyful Ones Are Not Yet Born,” but as the basis for a series of variations. Hurst’s bass provides single notes and chords of support, playing a gentle harmony in the head and then providing strummed, almost kora-like support under the improvisation. Branford improvises rhythmically, at first slowly but by the fourth peak in a spiraling frenzy. The title of the piece is taken from the 1968 novel of the same name by Ayi Kwei Armah, who wrote about conditions in a post-independence Ghana and the struggle of the narrator to find his way amidst corruption and decay. Branford’s work can be heard as a lament, if not a threnody, and by the time Tain’s drums crest like a wave under the soloist the lament has reached a fever pitch. Hurst’s solo plays melody and harmony at once, punctuated by the pulsing kora sounds as Branford returns to recapitulate the melody. It’s an engrossing listen even at 13+ minutes.

“Cain and Abel” sets up a conversation between two brothers, who by now had evolved to very different perspectives of what jazz could be. They play the head together, a melody that seems designed to disguise that it’s in 4/4 time, and quickly swing into a call-and-response, with Wynton making the opening statement and Branford responding—sometimes echoing, sometimes inverting, sometimes wryly commenting. At times it sounds like Wynton is winning some musical battle, but then Branford hits a lick back or inverts the harmony and we’re in a very different place. At the end Branford swings into a different key and mood entirely, and the horns end the piece in parallel harmonic descending arpeggios, landing in a different key as Bob Hurst supports them with a two-note ground that sounds as though they might be ready to start an entirely new tune. The whole thing swings all through thanks to Hurst and Tain’s shambolic rhythm work.

“Citizen Tain” has the strongest melody of the faster pieces on the record, consisting of a series of arpeggios in triple meter that swing into a fast four over Tain’s explosive drumming and Hurst’s ground bass. As the trio swings into the first variation, Hurst’s bass finally snaps out of its repeated accompaniment into a brisk walk, proving that basses can walk in time signatures other than 4/4. When the bassist takes a solo, it’s the first time we hear something other than the walk as he plays syncopated open fifths and sixths. The trio comes together at the end, doubling up on the triple-meter arpeggios into a fade-out.

“Gilligan’s Isle” is a free, slow ballad that bears no resemblance to the television show’s theme. The group’s musicianship means things are constantly in motion, but without a strong melody to latch onto it’s hard for me to find much to write about. “Beat’s Remark,” the other Bob Hurst tune on the record, has a stronger, wistful melody that’s doubled in the bass over a constantly moving roll of the tide of Tain’s drums. Hurst takes the first solo, sowing bits of the melody among a long swinging statement that ends in some high bass harmonics as Branford comes back in. The band double- and triple-times the melody but somehow seems to still shamble their way into a transformation, when at around the 7:45 mark Branford hits and holds a series of notes, playing a sort of “B” version of the original melody, and giving a quiet line interrupted only by one outburst note and supported by a series of suspended subtonics on the bass. The head returns, but the band seems to look around one more corner and find one more iteration of the melody to collectively improvise into, this time finding a rhythmic pattern that they ride into the end of the groove.

This is among the last of Branford’s run of recordings for Columbia Records that I can find on vinyl; the CD format had won by this point for many reasons, not least of which was the greater capacity offered. Case in point: the CD version contains two more tracks than present on this LP, “Xavier’s Lair” (continuing the X-Men theme begun in Crazy People Music, and “Dewey Baby,” a blistering tenor battle with English saxophonist Courtney Pine. The whole set is pure fire. I confess with some residual cringing that this is the second time I’ve reviewed this album; the first was for UVa’s alt-weekly The Declaration, and I am grateful that it has yet to be digitized because I seem to recall using words like “ceremonial dances around the fire” to describe how the music made me feel. Ultimately The Beautyful Ones Are Not Yet Born is about three musicians exploring how far they can take their music. It’s heady stuff, and I can only wonder what the Deadheads who might’ve picked it up thought.

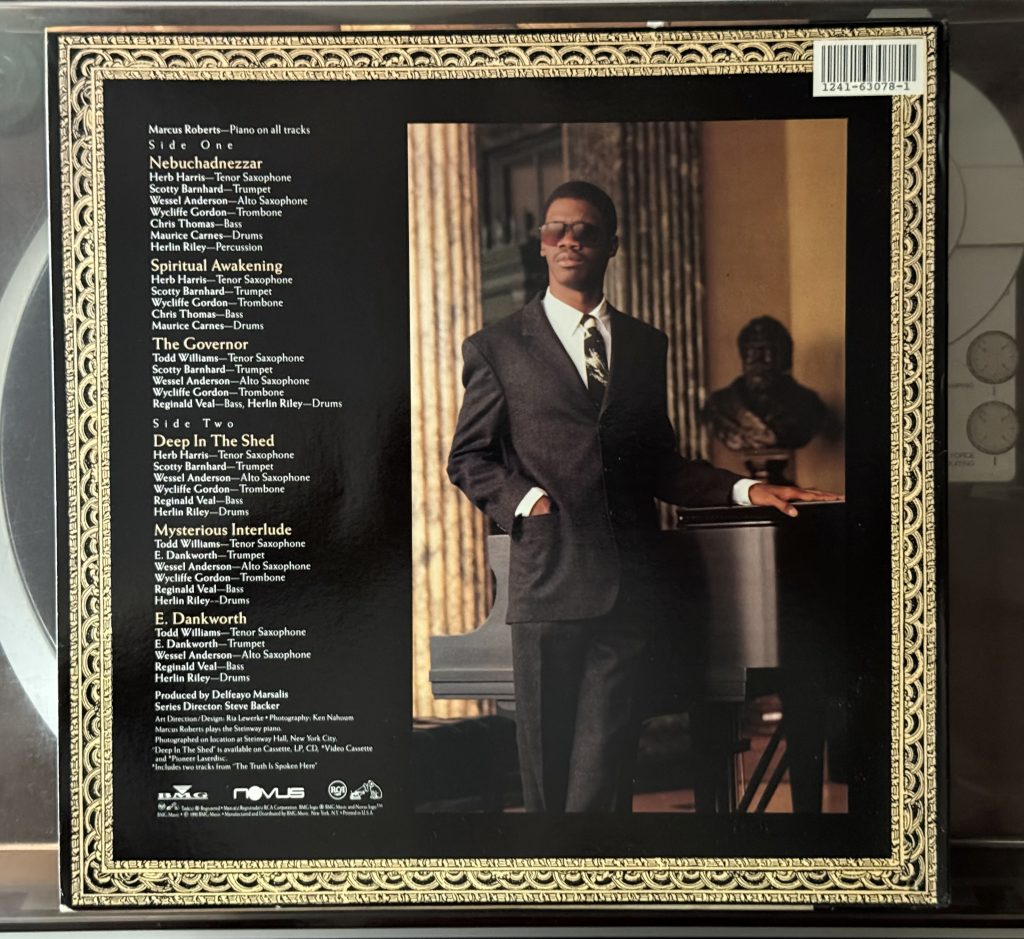

Branford had a few other surprises in him, and we’ll check them out in a couple weeks, but first we are going to check back in one last time with Marcus Roberts and find him in a very different context.

You can listen to this week’s album here:

BONUS: Branford’s live album with this trio, Bloomington, provides a technicolor window into the power of his compositions (and the players). Here’s the title track in its live version.

- In late 1990 and early 1991, Kenny seems to have been quite busy producing and performing on Charnett Moffat’s solo debut Nettwork, appearing on Jeff “Tain” Watts’ solo debut Megawatts, backing up UK tenor sax sensation Courtney Pine, and recording his own self-titled solo debut. It’s a little hard to tell because these albums don’t list recording dates, but it’s a safe assumption he was pretty busy. ↩︎